Tiny Archives: Metabolic Molecules Store the Prehistoric World

Breaking News:

Donnerstag, Dez. 18, 2025

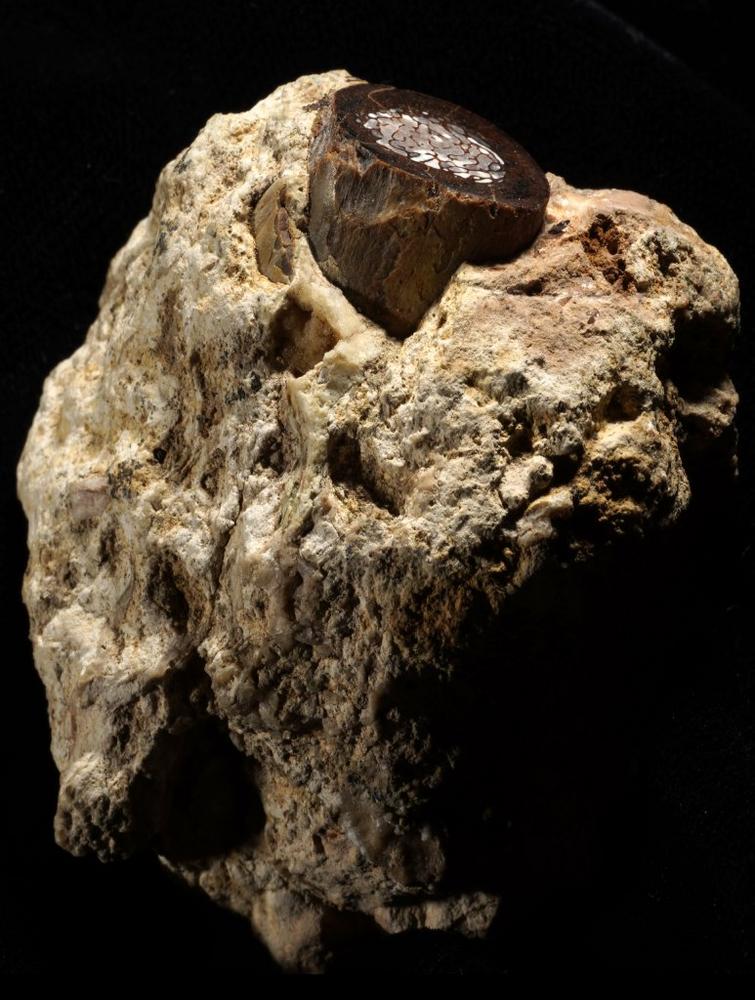

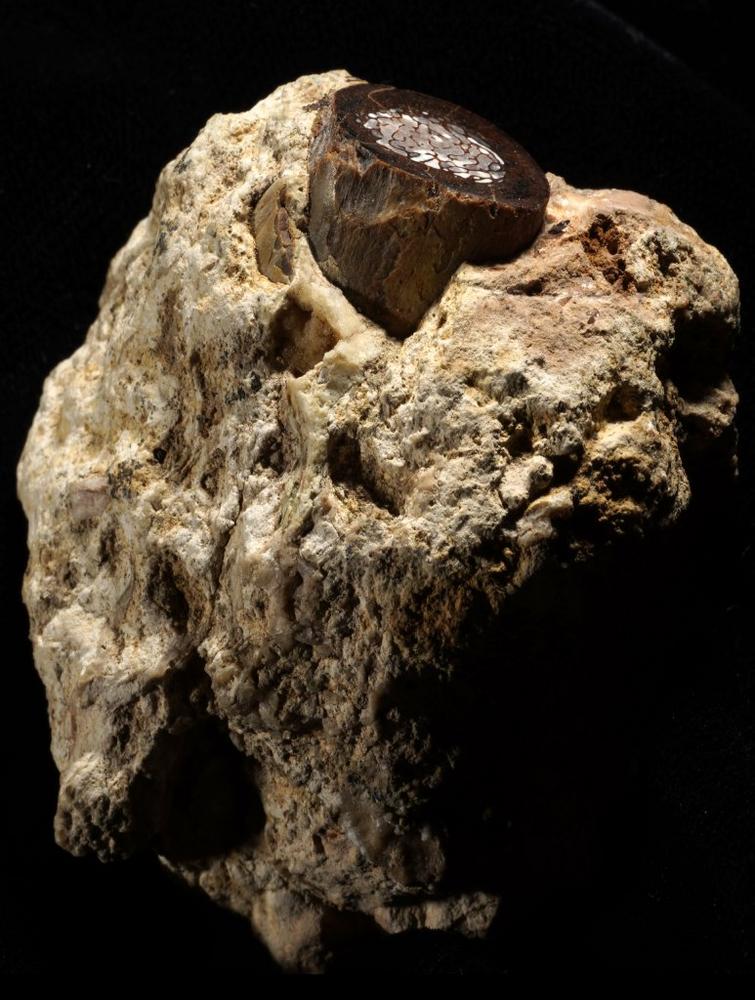

What did the environment of early humans look like around three to one million years ago – and what about the animals that lived there? An international research team, including Prof. Dr. Ottmar Kullmer from the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, has now used the innovative new method of “metabolomic profiling” to answer this question. The team examined fossils of animals from various sites and regions in Africa that are of great importance for the study of prehistoric humans, including samples from the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, the Chiwondo Beds in Malawi, and the Makapansgat cave site in South Africa. They focused on the question of whether molecular metabolites – small chemical compounds produced in the body or absorbed through food and the environment – can still be detected in the teeth and bones of rodents, pigs, elephants, and antelopes even after millions of years. Such metabolites can be used to determine how a living organism interacted with its environment.

“We were able to show that certain molecules are trapped during the formation of bones and teeth and are preserved there like in a tiny archive,” explains the study’s lead author, Prof. Timothy Bromage. “These traces of metabolic products originate both from the bodies of the animals themselves and from their environment, thereby providing important clues to biological functions and habitats.”

The analysis of the molecules opens a window into the past and makes it possible to narrow down earlier environmental conditions more precisely. The data from the Olduvai Gorge indicate a warmer climate than today and humid landscapes with forests, grasslands, and fresh water – both for the site’s older layers and for more recent sections. The sites in Malawi and South Africa also point to more humid and sometimes warmer conditions compared to today. These results support earlier environmental reconstructions and provide additional details, for example regarding soil composition, plant species, and precipitation levels.

In addition to environmental information, the researchers also found indications regarding the health of individual animals. Certain molecules can be linked to inflammation or infections. Some fossils also contained traces of a pathogen that today causes African sleeping sickness and is transmitted by the tsetse fly. “Such findings show that we can use this method to identify not only landscapes but also the risk of disease in past ecosystems,” explains Prof. Dr. Ottmar Kullmer, the study’s coauthor. “This expands our picture of the living conditions of early animals and, indirectly, early humans as well.”

The team took particular care to check whether the molecules found actually originated from inside the fossils or whether they could have infiltrated the samples later from the soil around them. To this end, the team analyzed surrounding soils and modern reference samples. The impact of digestive processes – for example in the case of bones from owl pellets – was also examined. The results show that the crucial molecules originate predominantly from the animals’ original tissue.

“Our study shows that ‘metabolomic profiling’ can be successfully and systematically applied to very old fossils. This opens up a completely new approach to reconstructing early habitats, which significantly complements previous methods such as isotope analyses or studies of animal communities,” says Kullmer, and he continues, “The method allows us to better understand the relationships between animals and their environment over the course of evolutionary history and to further complete our picture of the ecological conditions of the past.”

“Future research should also continue to expand the metabolic profiles of modern-day plants, soils, and microorganisms,” adds Bromage, and he concludes, “The better we know today’s ecosystems at a molecular level, the more precisely we can reconstruct past worlds.”

Publication

Bromage, T.G., Denys, C., De

Jesus, C.L. et al.

Palaeometabolomes yield biological

and ecological profiles at early

human sites. Nature (2025).

https://doi.org/…

025-09843-w

The Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung (Senckenberg Nature Society), a member institution of the Leibniz Association, has studied the “Earth System” on a global scale for over 200 years – in the past, in the present, and with predictions for the future. We conduct integrative “geobiodiversity research” with the goal of understanding nature with its infinite diversity, so we can preserve it for future generations and use it in a sustainable fashion. In addition, Senckenberg presents its research results in a variety of ways, first and foremost in its three natural history museums in Frankfurt, Görlitz, and Dresden. The Senckenberg natural history museums are places of learning and wonder and serve as open platforms for a democratic dialogue – inclusive, participative, and international. For additional information, visit www.senckenberg.de.

Senckenberg – Leibniz Institution for Biodiversity and Earth System Research // Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Senckenberganlage 25

60325 Frankfurt

Telefon: +49 (69) 7542-0

Telefax: +49 (69) 746238

http://www.senckenberg.de

![]()